|

|

Zachary Taylor was born in November of 1784 in Orange County Virginia. He was the second son of Colonel Richard Taylor, whose ancestors emigrated from England about two centuries ago, and settled in Eastern Virginia. The father, distinguished alike for patriotism and valor, served as colonel in the Revolutionary War, fighting in many important engagements. About 1790 he left his Virginia farm and emigrated with his family to Kentucky. It was in Kentucky that Zachary Taylor learned of the the trials incident to border life. The earliest impressions of young Zachary were the sudden foray of the savage foe, the piercing warwhoop, the answering cry of defiance, the gleam of the tomahawk, the crack of the rifle, the homestead saved by his father's daring, the neighboring cottage wrapped in flames, or its hearth-stone red with blood. Such scenes bound his young nerves with iron, and fired his fresh soul with martial ardor; working upon his superior nature they made arms his delight, and heroism his destiny. Zachary was placed in school at an early age, and his teacher remembered the qualities which made him a leader among his mates and a pride to his master.

After leaving school and soon after the murderous attack of the British ship Leopard upon the Chesapeake, in 1808, he entered the army as first lieutenant in the 7th Regiment of Infantry where he gained distinction in border skirmishes with the Indians, and, when the war broke out, he was promoted to the rank of captain. Within sixty days after the commencement of hostilities in 1812 and when the Michigan territory was lost to the enemy, he feared that this conquest would jeopard the whole northwestern region. Thus, Captain Taylor was given the command of Fort Harrison, which was situated on the Wabash in the very heart of the Indian country. The garrison consisted of only fifty men, of whom thirty were disabled by sickness, nevertheless, with this little handful of soldiers, the young commander immediately set about repairing the fortifications. He had hardly completed his work, when, on the night of the 4th of September, an alarm shot from one of his sentinels arousing him from a bed of fever. The task was to meet the attack of a large force of Miami Indians. Every man was at once ordered to his post. A contiguous blockhouse was fired by the enemy, and a thick discharge of bullets and arrows was opened upon the fort. The darkness of the night, the howlings of the savages, the shrieks of the women and children, the fast approaching flames, and the panic of the debilitated soldiers, made up a scene of terror. Taylor inspired his men with his own courage and energy. The flames were extinguished, the consumed breast-works were renewed, and volley answered volley for six long hours till day break enabled the Americans to aim with a deadly precision that soon dispersed their foes. This gallant improbable repulse prompted a report from Major General Hopkins to Governor Shelby that "the firm and almost unparalleled defense of Fort Harrison had raised for Captain Zachary Taylor a fabric of character not to be affected by eulogy." As a result, President Madison a preferred upon Taylor the rank of brevet major. It is said that this was the first brevet ever to be conferred in the American army.

After the war Taylor gained a victory in Florida of Okee-Chobee in 1837. The action was very severe, and continued nearly four hours. The Indians, under the command of Alligator and Sam Jones, numbered about 700 warriors, and were posted in a dense hammock, with their front covered by a small stream, almost impassable on account of quicksands, and with their flanks secured by swamps that prevented all access. The fore of Colonel Taylor, including inexperienced soldiers, consisted of some 500 men. Nevertheless, they crossed a stream and while sinking to the middle in the mire, passed under the galling fire of the enemy. A close and desperate fight ensued, during which the five companies of the 6th Infantry, who bore the brunt of the fray, lost every officer but one, and one of these companies saved only four privates unharmed. The line of the enemy was broken, and their right flank turned. They were soon scattered in all directions, and were pursued till near night. The American loss was 26 killed and 112 wounded; that of the Indians was very large, but never definitely ascertained. Throughout the whole engagement, Colonel Taylor was passing on his horse from point to point within the sweep of the Indian rifles, emboldening and directing his men, without the least apparent regard for his own personal safety. This victory had a decisive influence upon the turn of the war with the Indians; and the government immediately testified their sense of its importance by conferring upon its gallant winner the rank of brigadier-general by brevet. In May, General Taylor succeeded General Jesup in the command of the Florida army, and served in this capacity during two years quelling the atrocities of Indian warfare, and restoring peace and security to the southern frontier. In 1840, at his own request, he was relieved by Brigadier-general Armistead, and was ordered to the southwestern department. Here he remained at various head-quarters until government had occasion for his services in Texas.

When President Tyler started the annexation of Texas and an Act was passed in March of 1845 ratified by the Texas government. However, Mexico stoutly protested against the annexation and a special American was envoy sent to the Mexican capital to settle differences. However, it was refused a hearing and Mexico prepared for another invasion of Texas. In June, General Taylor received orders to advance with his troops over the Sabine, and protect all of the territory east of the Rio Grande, over which Texas exercised jurisdiction. He accordingly marched into Texas, and in August concentrated his forces, amounting to about 3000 men, at Corpus Christi. Receiving orders from Washington to proceed to the Rio Grande, the general, with his little army, moved westward in March, 1846: and after considerable suffering from the heal and the want of food and water, reached the banks of the river opposite Matamoras on the 28th of the month. Colonel Twiggs, with a detachment of dragoons, in the mean time took possession of Point Isabel, situated on an arm of the Gulf, about 25 miles east. General Taylor took every means to assure the Mexicans that his purpose was not war, nor violence in any shape, but solely the occupation of the Texian territory to the Rio Grande, until the boundary should be definitively settled by the two republics.

After encamping opposite Matamoras, the American general prepared with great activity for Mexican aggression, by erecting fortifications, and planting batteries. The Mexicans speedily evinced hostile intentions. General Ampudia arrived at Matamoras with 1000 cavalry and 1500 infantry, and made overtures to our foreign soldiers to "separate from the Yankee bandits, and array themselves under the tricolored flag!" The American general was summoned to withdraw his forces at the penalty of being treated as an enemy, but he stood his ground. Meanwhile, General Arista soon arrived at Matamoras, and, superseding Ampudia, issued a proclamation to the American soldiers, begging them not to be the "blind instruments of unholy and mad ambition, and rush on to certain death," then sent a large body of troops over the river to cut off all communication between General Taylor and his depot at Point Isabel. A detachment of 61 soldiers under Captain Thornton, was waylaid by a Mexican force of ten times their number, and after a bloody conflict and the loss of many lives, was obliged to surrender. They only had rations sufficient for eight days. Meanwhile, the country to the East fast filling up with the Mexican troops. General Taylor resolved to procure additional supplies despite the hazards; and, leaving the fort under the command of Major Brown, he set out with a large portion of his army for Point Isabel. He reached that place the next day without molestation. Soon after his departure, the Mexicans opened their batteries upon Fort Brown. The fire was steadily returned with two long eighteen and sixteen brass six pounders by the garrison, which numbered about 900 men. The bombardment of the fort was kept up at intervals from batteries in its rear, as well as from the town, for six days. The Americans, though possessed of little ammunition, and having to mourn the fall of their gallant commander, sustained the cannonade with unyielding firmness until the afternoon of the 8th, when their hearts were thrilled with exultation by the answering peals of General Taylor at Palo Alto.

On the evening of the 7th, the American general, with about 2000 men and 250 wagons left Point Isabel for the relief of Fort Brown, and after advancing seven miles encamped. The next morning he resumed his march, and at noon met 6000 Mexican troops under Arista, with 800 cavalry, and seven field-pieces in the line of battle, flanked at both sides by small pools, and partly covered in front by thickets of chaparral and Palo Alto. General Taylor at once halted, refreshed his men, advanced to within a quarter of a mile of the Mexican line, and gave battle. The conflict first commenced between the artillery, and for two hours the batteries of Ringgold, Duncan and Churchill mowed down rank after rank of the enemy. The infantry remained idle spectators until General Torrejon, with a body of lancers, made a sally upon our train. The advancing columns were received with a tremendous fire, and faltered, broke, and fled. The battle raged on amid a lurid cloud of smoke from the artillery and the burning grass of the prairie. It rested for an hour, and then again moved on. As the American batteries opened with more force than ever, the ranks of the enemy were broken only to be refilled by fresh men. Captain May charged upon the left, but with too few men to be successful. The chivalrous Ringgold fell. The cavalry of the enemy advanced upon our artillery of the right to within close range, when a storm of cannister swept them back like a tornado. Their infantry made a desperate onset upon our infantry, but recoiled before their terrible reception. Again they rallied, and again were they repulsed. Panic seized the baffled foe, and soon squadron and column were in fall retreat. The conflict had lasted five hours, with a loss to the Americans of 7 killed and 37 wounded, and to the Mexicans of at least 250 killed and wounded.

In the evening, a council of war was held upon the propriety of persisting to advance upon Fort Brown in spite of the vastly superior force of the enemy. Of the thirteen officers present some were for retreating to Point Isabel, others for intrenching upon the spot, and only four for pushing ahead. The general, after hearing all opinions, settled the question by the laconic declaration, "I will be at Fort Brown before to-morrow night if I live." In the morning the army again marched.

The enemy were again met most advantageously posted in the ravine of Resaca de la Palma within three miles of Fort Brown. About 4 p.m. the battle commenced with great fury. The artillery on both sides did terrible execution. By order of General Taylor, May, with his dragoons, charged the batteries of the enemy. The Mexicans reserved their fire until the horses were near the cannons' mouth, and then poured out a broadside which laid many a proud fellow low. Those of the dragoons not disabled rushed on, overleaped the batteries, and seized the guns. The enemy recoiled, again rallied, and with fixed bayonets returned to the onset. Again they were repulsed. The "Tampico veterans" came to the rescue, were met by the dragoons now reinforced with infantry, and all but seventeen fell sword in hand after fighting with the most desperate bravery. This decided the battle. The flanks of the enemy were turned, and soon the rout became general. The Mexicans fled to the flat boats of the river, and the shouts of the pursuers and the shrieks of the drowning closed the scene. A great number of prisoners including 14 officers, eight-pieces of artillery, and a large quantity of camp equipage fell into the hands of the victors. The American loss was 39 killed and 71 wounded; that of the enemy in the two actions was at least 1000 killed and wounded. Fort Brown was relieved, and the next day Barita on the Mexican bank was taken by Colonel Wilson without resistance. The victories of the 8th and 9th filled the country with excitement and the American government acknowledged the distinguished services of General Taylor by making him Major-general by brevet; Congress passed resolutions of high approval; Louisiana presented him with a sword, and the press every where teemed with his praise.

As soon as means could be procured, General Taylor crossed the Rio Grande, took Matamoras without opposition, and made Colonel Twiggs its governor. The army soon received large volunteer reinforcements, and on the 5th of August the American general left Matamoras for Camargo, and thence proceeded through Seralos to Monterey, where he arrived the 19th of September. The Mexicans, under General Ampudia had placed this strongly fortified town in a complete state of defense. Not only were the walls and parapets lined with cannons, but the streets and houses were barricaded and planted with artillery. The bishop's palace on a hill at a short distance west of the city was converted into a perfect fortress. The town was well supplied with ammunition, and manned with 7000 troops of the line, and from 2000 to 3000 irregulars. The attack commenced on the 21st, and two important redoubts without the city, and an important work within, were carried with a loss to the Americans in killed and wounded of not less than 394. At three the next morning, a considerable force under General Worth dragged their howitzers by main strength up the hill, and assaulted the palace. The enemy made a desperate sortie, but were driven back in confusion, and the fortification was soon taken by the Americans with a loss of only 7 killed and 12 wounded. The next night, the Mexicans evacuated nearly all their defenses in the lower part of the city. The Americans entered the succeeding day, and by the severest fighting slowly worked their way from street to street and square to square, until they reached the heart of the town. General Ampudia saw that further resistance was useless, and, on the morning of the 24th, proposed to evacuate the city on condition that he might take with him the personel and materiel of his army. This condition was refused by the American general. A personal interview between the two commanders ensued, which resulted in a capitulation of the city, allowing the Mexicans to retire with their forces and a certain portion of their materiel beyond the line formed by the pass of the Rinconada and San Fernando de Presas and engaging the Americans not to pass beyond that line for eight weeks. Our entire loss during the operations was 12 officers and 108 men killed, 31 officers and 337 men wounded; that of the enemy is not known, but was much larger. The terms accorded by the conqueror were liberal, and dictated by a regard to the interests of peace; they crowned a gallant conquest of arms with a more sublime victory of magnanimity.

General Taylor could not long remain inactive, and with a bold design to seek out the enemy and fight him on his own ground, he marched as far as Victoria. But by the transfer of the seat of the war to Vera Cruz, he was deprived of the greater portion of his army, and was obliged to fall back on Monterey. Here he remained until February, when, having received large reinforcements of volunteers, he marched at the head of 4,500 men, to meet Santa Anna; and on the 20th, took up a position at Buena Vista, the great advantages of which had previously struck his notice. On the 22d, a Mexican army of 20,000 made its appearance, and Santa Anna summoned the American commander to surrender. General Taylor, with Spartan brevity, "declined acceding to the request." The next morning a conflict which lasted ten hours began. It was a fearful battle which is written forever upon the memory of the nation. The advance of the hostile host with muskets and swords and bayonets gleaming in the morning sun; the shouts of the marshaled foemen; the opening roar of the artillery; the sheeted fire of the musketry; the unchecked approach of the enemy; the outflanking by their cavalry and its concentration in our rear; the immovable fortitude of the Illinoians; the flight of the panic-stricken Indianians; the fall of Lincoln; the wild shouts of Mexican triumph; the deadly and successful charge upon the battery of O'Brien; the timely arrival of General Taylor from Saltillo, and his composed survey, amid the iron hail, of the scene of battle; the terrible onset of the Kentuckians and Illinoians; the simultaneous opening of the batteries upon the Mexican masses in the front and the rear; the impetuous but ill-fated charge of their cavalry upon the rifles of Mississippi; the hemming-in of that cavalry, and the errand of Lieutenant Crittenden to demand of Santa Anna its surrender; the response of the confident chieftain by a similar demand; the immortal rejoinder, "General Taylor never surrenders!" the escape of the cavalry to a less exposed position; its baffled charge upon the Saltillo train; its attack upon the hacienda, and its repulse by the horse of Kentucky and Arkansas; the fall of Yell and Vaughan, the insolent mission, under a white flag, to inquire what General Taylor was waiting for; the curt reply "for General Santa Anna to surrender;" the junction, by this ruse, of the Mexican cavalry in our rear with their main army; the concentrated charge upon the American line; the overpowering of the battery of O. Brien; the fearful crisis; the reinforcement of Captain Bragg "by Major Bliss and I;" the "little more grape, Captain Bragg;" the terrific carnage; the pause, the advance, the disorder, and the retreat; the too eager pursuit of the Kentuckians and Illinoians down the ravines; the sudden wheeling around of the retiring mass; the desperate struggle, and the fall of Harden, McKee, and Clay; the imminent destruction, and the rescuing artillery; the last breaking and scattering of the Mexican squadrons and battalions; the joyous embrace of Taylor and Wool; and Old Rough and Ready "Tis impossible to whip us when we all pull together;" the arrival of cold nightfall; the fireless, anxious, weary bivouac. The American loss was 267 killed, 456 wounded, and 23 missing. The Mexicans left 500 dead on the field, and the whole number of their killed and wounded was probably near 2000.

The victory of Buena Vista was the last and crowning achievement of General Taylor's military life. His department in Mexico was entirely reduced by it to subjection, and the subsequent operations of his army were few and unimportant. At the close of the war he retired from Mexico, carrying with him not only the adoration of his soldiers, but even the respect and attachment of the very people he had vanquished. Louisiana welcomed him with an ovation of the most fervent enthusiasm. Thrilling eloquence from her most gifted sons, blessings, and smiles, and wreaths from her fairest daughters, overwhelming huzzas from her warm-hearted multitudes, triumphal arches, splendid processions, costly banners, sumptuous festivals, and, in short, every mode of testifying love and homage was employed; but modesty kept her wonted place in his heart, and counsels of peace were, as ever, on his tongue. His prowess in conflict was no more admirable than his self-forgetfulness in triumph.

His last great deed had hardly ceased to echo over the land, before the people began to note his distinguishing career and insisted that he be named for the Presidency. During the political contest he remained steadfastly true to himself. He neither stooped nor swerved, neither sought nor shunned. He was borne by a triumphant majority to the Presidential chair, and in a way that has impelled the most majestic intellect of the nation to declare, that "no case ever happened in the very best days of the Roman Republic, where any man found himself clothed with the highest authority of the State, under circumstances more repelling all suspicion of personal application, all suspicion of pursuing any crooked path in politics, or all suspicion of having been actuated by sinister views and purposes."

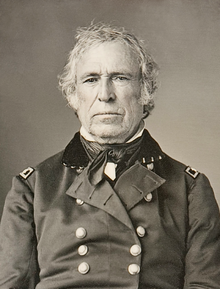

President Zachary Taylor stood about five feet eight inches in height with gray hair, plain features but eyes full of firmness, intelligence, and benevolence. His manners were easy and cordial, his dress, habits, and tastes simple, and his style of living temperate in the extreme. His speeches and his official papers, both military and civil, are alike famed for their propriety of feeling and their chastity of diction. His private life was unblemished, and the loveliness of his disposition made him the idol of his own household and the favorite of all who knew him. His martial courage was only equaled by his Spartan simplicity, his unaffected modesty, his ever wakeful humanity, his inflexible integrity, his uncompromising truthfulness, his lofty magnanimity, his unbounded patriotism, and his unfaltering loyalty to duty. His mind was of an original and solid cast, admirably balanced, and combining the comprehensiveness of reason with the penetration of instinct. Its controlling element was a strong, sterling sense, that of itself rendered him a wise counselor and a safe leader. All of his personal attributes and antecedents made him pre-eminently a man of the people, and remarkably qualified him to be the stay and surety of his country in this its day of danger. Zachary Taylor was the 12th President of the United States, serving from March 1849 until his death on July 3, July 1850. Confronting Death with the fearless declaration, "I am prepared; I have endeavored to do my duty,"