HISTORY

AND

COMPREHENSIVE

DESCRIPTION

OF

BY

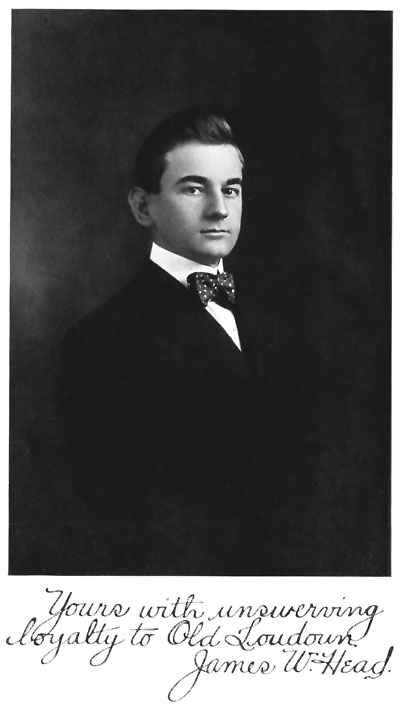

JAMES

W. HEAD

PARK VIEW PRESS

Copyright 1908

by JAMES W. HEAD

|

Dedication. |

|

|

|

TO MY MOTHER, |

|

|

|

WHOSE LOVE FOR LOUDOUN

IS NOT LESS ARDENT |

"So much, then, to show briefly that

Loudoun County life is a little out of the ordinary, here in America, and hence

worth talking about. There are other communities in

|

|

Pages. |

|

9-14 |

|

|

|

|

|

15-16 |

|

|

16-18 |

|

|

18-20 |

|

|

21-22 |

|

|

22-25 |

|

|

25-26 |

|

|

26-44 |

|

|

26-30 |

|

|

30 |

|

|

30-32 |

|

|

32-34 |

|

|

34-36 |

|

|

36-38 |

|

|

38-39 |

|

|

39-40 |

|

|

40-41 |

|

|

41-44 |

|

|

44-49 |

|

|

49-66 |

|

|

49-52 |

|

|

53-54 |

|

|

54-55 |

|

|

55-56 |

|

|

56-58 |

|

|

58-59 |

|

|

59-60 |

|

|

60-62 |

|

|

62-63 |

|

|

63-64 |

|

|

64-65 |

|

|

65-66 |

|

|

66 |

|

|

67-69 |

|

|

67-68 |

|

|

68-69 |

|

|

69-71 |

|

|

71-79 |

|

|

71-74 |

|

|

74-75 |

|

|

75 |

|

|

75 |

|

|

75-76 |

|

|

76 |

|

|

76 |

|

|

76-77 |

|

|

77-79 |

|

|

|

|

|

81-83 |

|

|

83-87 |

|

|

87-91 |

|

|

91-93 |

|

|

94-97 |

|

|

94 |

|

|

94 |

|

|

95 |

|

|

95-96 |

|

|

96 |

|

|

96 |

|

|

96-97 |

|

|

97 |

|

|

97 |

|

|

98-100 |

|

|

98 |

|

|

98 |

|

|

98-99 |

|

|

99 |

|

|

99 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

101-102 |

|

|

101 |

|

|

101-102 |

|

|

102-105 |

|

|

102-104 |

|

|

104-105 |

|

|

|

|

|

107-109 |

|

|

109-110 |

|

|

110-113 |

|

|

113-123 |

|

|

113-115 |

|

|

116-120 |

|

|

120-123 |

|

|

123-124 |

|

|

124-127 |

|

|

124-125 |

|

|

125-127 |

|

|

127-138 |

|

|

127 |

|

|

127-129 |

|

|

130-131 |

|

|

131-132 |

|

|

132-133 |

|

|

133-134 |

|

|

134-135 |

|

|

135-137 |

|

|

138 |

|

|

138-139 |

|

|

138-139 |

|

|

139 |

|

|

140 |

|

|

141-142 |

|

|

142-144 |

|

|

144 |

|

|

145-180 |

|

|

145-148 |

|

|

149-151 |

|

|

151-153 |

|

|

153-157 |

|

|

157 |

|

|

158-164 |

|

|

164-165 |

|

|

165-169 |

|

|

169-171 |

|

|

171-174 |

|

|

174-175 |

|

|

176-177 |

|

|

177-179 |

|

|

179-180 |

|

|

180-186 |

|

|

180-183 |

|

|

183-186 |

|

|

186 |

know not when I first

planned this work, so inextricably is the idea interwoven with a fading

recollection of my earliest aims and ambitions. However, had I not been

resolutely determined to conclude it at any cost—mental, physical, or

pecuniary—the difficulties that I have experienced at every stage might have

led to its early abandonment.

The greatest difficulty lay in procuring material

which could not be supplied by individual research and investigation. For this

and other valid reasons that will follow it may safely be said that more than

one-half the contents of this volume are in the strictest sense original, the

remarks and detail, for the most part, being the products of my own personal

observation and reflection. Correspondence with individuals and the State and

National authorities, though varied and extensive, elicited not a half dozen

important facts. I would charge no one with discourtesy in this particular, and

mention the circumstance only because it will serve to emphasize what I shall

presently say anent the scarcity of available material.

Likewise, a painstaking perusal of more than two

hundred [10]volumes yielded only meagre

results, and in most of these illusory references I found not a single fact

worth recording. This comparatively prodigious number included gazeteers,

encyclopedias, geographies, military histories, general histories, State and

National reports, journals of legislative proceedings, biographies,

genealogies, reminiscences, travels, romances—in

short, any and all books that I had thought calculated to shed even the

faintest glimmer of light on the County's history, topographical features, etc.

But, contrary to my expectations, in many there

appeared no manner of allusion to

That works of history and geography can be

prepared in no other way, no person at all acquainted with the nature of such

writings need be told. "As well might a traveler presume to claim the

fee-simple of all the country which he has surveyed, as a historian and geographer

expect to preclude those who come after him from making a proper use of his labors. If the former writers have seen accurately and

related faithfully, the latter ought to have the resemblance of declaring the

same facts, with that variety only which nature has enstamped upon the distinct

elaborations of every individual mind.... As works of this sort become

multiplied, voluminous, and detailed, it becomes a duty to literature to

abstract, abridge, and give, in synoptical views, the information that is spread

through numerous volumes."

Touching the matter gleaned from other books, I

claim the sole merit of being a laborious and faithful compiler. In some

instances, where the thoughts could not be better or more briefly expressed,

the words of the original authors may have been used.

Where this has been done I have, whenever

possible, made, in my footnotes or text, frank and ample avowal of the sources

from which I have obtained the particular information presented. This has not

always been possible for the reason [11]that I could not name, if disposed, all the sources from which I

have sought and obtained information. Many of the references thus secured have

undergone a process of sifting and, if I may coin the couplet, confirmatory

handling which, at the last, rendered some unrecognizable and their origin

untraceable.

The only publication of a strictly local color

unearthed during my research was Taylor's Memoir of Loudoun, a small

book, or more properly a pamphlet, of only 29 pages, dealing principally with

the County's geology, geography, and climate. It was written to accompany the

map of

I wish to refer specially to the grateful

acknowledgment that is due Arthur Keith's Geology of the Catoctin Belt

and Carter's and Lyman's Soil Survey of the Leesburg Area, two

Government publications, published respectively by the United States Geological

Survey and Department of Agriculture, and containing a fund of useful

information relating to the geology, soils, and geography of about two-thirds

of the area of Loudoun. Of course these works have been the sources to which I

have chiefly repaired for information relating to the two first-named subjects.

Without them the cost of this publication would have been considerably

augmented. As it is I have been spared the expense and labor that would have

attended an enforced personal investigation of the County's soils and geology.

And now a tardy and,

perhaps, needless word or two in revealment of the purpose of this volume.

To rescue a valuable miscellany of facts and

occurrences from an impending oblivion; to gather and fix certain ephemeral

incidents before they had passed out of remembrance; to render some account of

the County's vast resources and capabilities; to trace its geography and

analyze its soils and geology; to follow the tortuous windings of its numerous

streams; to chronicle the multitudinous deeds of sacrifice and daring performed

by her citizens and soldiery—such has been the purpose of this work, such its

object and design.[12]

But the idea as originally evolved contemplated

only a chronology of events from the establishment of the County to the present

day. Not until the work was well under way was the matter appearing under the

several descriptive heads supplemented.

From start to finish this self-appointed task

has been prosecuted with conscientious zeal and persistency of purpose,

although with frequent interruptions, and more often than not amid

circumstances least favorable to literary composition. At the same time my

hands have been filled with laborious avocations of another kind.

What the philosopher Johnson said of his great Dictionary

and himself could as well be said of this humble

volume and its author:

"In this work, when it shall be found that

much is omitted, let it not be forgotten that much likewise is performed; and

though no book was ever spared out of tenderness to the author, and the world

is little solicitous to know whence proceeded the faults of that which it

condemns; yet it may gratify curiosity to inform it, that the English

Dictionary was written with little assistance of the learned, and without

any patronage of the great; not in the soft obscurities of retirement, or under

the shelter of academick bowers, but amidst inconvenience and distraction, in

sickness and in sorrow."

If further digression be allowable I might say

that in the preparation of this work I have observed few of the restrictive

rules of literary sequence and have not infrequently gone beyond the prescribed

limits of conventional diction. To these transgressions I make willing

confession. I have striven to present these sketches in the most lucid and

concise form compatible with readableness; to compress the greatest possible

amount of useful information into the smallest compass. Indeed, had I been

competent, I doubt that I would have attempted a more elaborate rendition, or

drawn more freely upon the language and the coloring of poetry and the

imagination. I have therefore to apprehend that the average reader [13]will find them too

statistical and laconic, too much abbreviated and void of detail.

However, a disinterested historian I have not

been, and should such a charge be preferred I shall look for speedy exculpation

from the discerning mass of my readers.

In this connection and before proceeding further

I desire to say that my right to prosecute this work can not fairly be

questioned; that a familiar treatment of the subject I have regarded as my

inalienable prerogative. I was born in

But to return to my

theme.

I have a distinct foresight of the views which some will entertain and express

in reference to this work, though my least fears of criticism are from those

whose experience and ability best qualify them to judge.

However, to the end that criticism may be

disarmed even before pronouncement, the reader, before condemning any

statements made in these sketches that do not agree with his [14]preconceived opinions,

is requested to examine all the facts in connection therewith. In so doing it

is thought he will find these statements correct in the main.

In such a variety of subjects there must of

course be many omissions, but I shall be greatly disappointed if actual errors

are discovered.

In substantiation of its accuracy and

thoroughness I need only say that the compilation of this work cost me three

years of nocturnal application—the three most ambitious and disquieting years

of the average life. During this period the entire book has been at least three

times rewritten.

In the best form of which I am capable the

fruits of these protracted labors are now committed to the candid and, it is

hoped, kindly judgment of the people of

James W. Head.

"

SITUATION.

[1] "

The particular geographic location of Loudoun

has been most accurately reckoned by Yardley Taylor, who in 1853 made a

governmental survey of the county. He placed it "between the latitudes of

38° 52-1/2" and 39° 21" north latitude, making 28-1/2" of

latitude, or 33 statute miles, and between 20" and 53-1/2" of

longitude west from Washington, being 33-1/2" of longitude, or very near

35 statute miles."

Loudoun was originally a part of the six million

acres which, in 1661, were granted by Charles II, King of England, to Lord

Hopton, Earl of St. Albans, Lord Culpeper, Lord Berkeley, Sir William Morton,

Sir Dudley Wyatt, and Thomas Culpeper. All the territory lying between the

Rappahannock and

"The only conditions attached to the

conveyance of this domain, the equivalent of a principality, were that

one-fifth of all the gold and one-tenth of all the silver discovered within its

limits should be reserved for the royal use, and that a nominal rent of a few

pounds sterling should be paid into the treasury at Jamestown each year. In

1669 the letters patent were surrendered by the existing holders and in their

stead new ones were issued.... The terms of these letters required that the whole

area included in this magnificent gift should be planted and inhabited by the

end of twenty-one years, but in 1688 this provision was revoked by the King as

imposing an impracticable condition."[2]

[2] Bruce's Economic History of

The patentees, some years afterward, sold the

grant to the second Lord Culpeper, to whom it was confirmed by letters patent

of King James II, in 1688. From Culpeper the rights and privileges conferred by

the original grant descended through his daughter, Catherine, to her son, Lord

Thomas Fairfax, Baron of Cameron—a princely heritage for a young man of 20

years.

The original boundaries of

1. Be it enacted by the General Assembly,

That all that part of the county of Loudoun lying between the lower boundary

thereof, and a line to be drawn from the mouth of Sugar Land run, to Carter's

mill, on Bull run, shall be, and is hereby added to and made part of the county

of Fairfax: Provided always, That it shall be lawful for the sheriff of the

said county of Loudoun to collect and make distress for any public dues or

officers fees, which shall remain unpaid by the inhabitants of that part of the

said county hereby added to the county of Fairfax, and shall be accountable for

the same in like manner as if this act had not been made.

2. And be it further enacted, That it

shall be lawful for a majority of the acting justices of the peace for the said

county of Fairfax, together with the justices of the county of Loudoun included

within the part thus added to the said county of Fairfax, and they are hereby

required at a court to be held in the month of April or May next, to fix on a

place for holding courts therein at or as near the center thereof (having regard

to that part of the county of Loudoun hereby added to the said county of

Fairfax) as the situation and convenience will admit of; and thenceforth

proceed to erect the necessary public buildings at such place, and until such

buildings be completed, to appoint any place for holding courts as they shall

think proper.

3. This act shall commence and be in force from

and after the passing thereof.

As at present bounded, the old channel at the

mouth of

[3] "What is called Lowe's

Island, at the mouth of Sugarland Run, was formerly an island, and made so by

that run separating and part of it passing into the river by the present

channel, while a part of it entered the river by what is now called the old

channel. This old channel is now partially filled up, and only receives the

waters of Sugarland Run in times of freshets. Occasionally when there is high

water in the river the waters pass up the present channel of the run to the old

channel, and then follow that to the river again. This old channel enters the

river immediately west of the primordial range of rocks, that impinge so

closely upon the river from here to Georgetown, forming as they do that series

of falls known as Seneca Falls, the Great, and the Little Falls, making

altogether a fall of 188 feet in less than 20 miles."—Memoir of Loudoun.

[4] Designated in an old record as

a "double-bodied poplar tree standing in or near the middle of the

thoroughfare of Ashby's Gap on the top of the

This completes an outline of 109 miles, viz: 19

miles in company with

The main valleys are longitudinal and those

running transversely few and comparatively unimportant.

The far-famed Loudoun valley, reposing

peacefully between the Blue Ridge and

The Blue Ridge, the southeasternmost range of

the Alleghanies or Appalachian System presents here that uniformity and general

appearance which characterizes it throughout the [19]State, having gaps or depressions every eight or ten miles,

through which the public roads pass. The most important of these are the

Potomac Gap at 500 feet and Snickers and Ashby's Gap, both at 1,100 feet. The

altitude of this range in Loudoun varies from 1,000 to 1,600 feet above

tide-water, and from 300 to 900 feet above the adjacent country. It falls from

1,100 to 1,000 feet in 4 miles south of the river, and then, rising sharply to

1,600 feet, continues at the higher series of elevations. The Blue Ridge

borders the county on the west, its course being about south southwest, or

nearly parallel with the Atlantic Coast-line, and divides Loudoun from

Of nearly equal height and similar features are

the Short Hills, another range commencing at the Potomac River about four miles

below Harpers Ferry and extending parallel to the Blue Ridge, at a distance of

nearly four miles from summit to summit, for about twelve miles into the

County, where it is broken by a branch of Catoctin Creek. Beyond this stream it

immediately rises again and extends about three miles further, at which point

it abruptly terminates.

A third range, called "Catoctin

Mountain," has its inception in Pennsylvania, traverses Maryland, is

interrupted by the Potomac, reappears in Virginia at the river margin, opposite

Point of Rocks, and extends through Loudoun County for a distance of twenty or

more miles, when it is again interrupted.

Elevations on

Probably this mountain does not exceed an

average of more than 300 feet above the surrounding country, though at some

stages it may attain an altitude of 700 feet. Rising near the Potomac into one

of its highest peaks, in the same range it becomes alternately depressed and

elevated, until [20]reaching the point of its divergence in the neighborhood

of

On reaching the Leesburg and Snicker's Gap

Turnpike road, a distance of twelve miles, it expands to three miles in width

and continues much the same until broken by Goose Creek and its tributary, the

North Fork, when it gradually loses itself in the hills of Goose Creek and

Little River, before reaching the Ashby's Gap Turnpike.

The Catoctin range throughout Loudoun pursues a

course parallel to the

Immediately south of Aldie, on Little River,

near the point of interruption of

East of the Catoctin the tumultuous continuity

of mountains subsides into gentle undulations, an almost unbroken succession of

sloping elevations and depressions presenting an as yet unimpaired variety and

charm of landscape. However, on the extreme eastern edge of this section, level

stretches of considerable extent are a conspicuous feature of the topography.

Three or four detached hills, rising to an

elevation of 150 or 200 feet above the adjacent country, are the only ones of

consequence met with in this section.[21]

The hilly character of Loudoun is clearly shown

by the following exhibit of the elevation of points and places above

tide-water. The variations of altitude noted in this schedule are based upon

conflicting estimates and distinct measurements made at two or more points

within a given circumference and slightly removed one from the other.

|

|

|

|

|

Feet. |

|

|

|

|

|

415 |

|

Ashburn |

|

|

|

320 |

|

Leesburg |

|

|

|

321 to 337 |

|

Clarke's Gap |

|

|

|

578 to 634 |

|

|

|

|

|

454 to 521 |

|

Purcellville |

|

|

|

546 to 553 |

|

Round Hill |

|

|

|

558 |

|

Bluemont |

|

|

|

680 to 730 |

|

Snicker's Gap |

|

|

|

1,085 |

|

Neersville |

|

|

|

626 |

|

Hillsborough |

|

|

|

550 |

|

|

|

|

|

360 |

|

|

|

|

|

600 |

|

Oatlands |

|

|

|

270 |

|

Little River, near Aldie |

|

|

|

299 |

|

Middleburg |

|

|

|

480 |

|

|

|

|

|

188 |

|

|

|

|

|

200 |

|

|

|

|

|

246 |

The whole of the county east of the

The Short Hills have an approximate altitude of

1,000 feet, while that of the

From many vantage points along the

The drainage of Loudoun can be divided into two

provinces. One is the

The tributaries by which the drainage of the two

provinces is effected are Catoctin Creek, North Fork Catoctin Creek, South Fork

Catoctin Creek, Little River, North Fork Goose Creek, Beaver-dam Creek, Piney

Run, Jeffries Branch, Cromwells Run, Hungry Run, Bull Run, Sycoline Creek,

Tuscarora Creek, Horse Pen Run, Broad Run, Sugarland Run, Elk Lick, Limestone

Branch, and as many lesser streams.[23]

The general slope of the county being to the

northeast, the waters, for the most part, naturally follow the same course, as

may be readily perceived by reference to maps of the section. The streams that

rise in the Blue Ridge mostly flow to the eastward until they approach the

Catoctin Creek is very crooked; its basin does

not exceed twelve miles as the crow flies, and includes the whole width of the

valley between the mountains except a small portion in the northeastern angle

of the County. Yet its entire course, measuring its meanders, would exceed

thirty-five miles. It has a fall of one hundred and eighty feet in the last

eighteen miles of its course, and is about twenty yards wide near its mouth.

The Northwest Fork rises in the Blue Ridge and

flows southeastward, mingling its waters with the Beaver Dam, coming from the

southwest, immediately above

Little River, a small affluent of Goose Creek,

rises in Fauquier County west of Bull Run mountain and enters Loudon a few

miles southwestward of Aldie. It pursues a northern and northeastern course

until it has passed that town, turning then more to the northward and falling

into

Broad Run, the next stream of consequence east

of

Sugarland Run, a still smaller stream, rises

partly in Loudoun, though its course is chiefly through

In its southeastern angle several streams rise

and pursue a southern and southeastern course, and constitute some of the upper

branches of

Perhaps no county in the State is better watered

for all purposes, except manufacturing in times of drought. Many of the farms

might be divided into fields of ten acres each and, in ordinary seasons, would

have water in each of them.

There are several mineral springs in the county

of the class called chalybeate, some of which contain valuable medicinal

properties, and other springs and wells that are affected with lime. Indeed, in

almost every part of the County, there is an exhaustless supply of the purest

spring water. This is due, in great part, to the porosity of the soil which

allows the water to pass freely into the earth, and the slaty character of the

rocks which favors its descent into the bowels of the hills, from whence it

finds its way to the surface, at their base, in numberless small springs. The

purity of these waters is borrowed from the silicious quality of the soil.

The largest spring of any class in the county is

Big Spring, a comparatively broad expanse of water of unsurpassed quality,

bordering the Leesburg and Point of Rocks turnpike, about two miles north of

Leesburg.[25]

The springs, as has been stated, are generally

small and very numerous, and many of them are unfailing, though liable to be

affected by drought. In such cases, by absorption and evaporation, the small

streams are frequently exhausted before uniting and often render the larger

ones too light for manufacturing purposes. Nevertheless, water power is

abundant; the county's diversified elevation giving considerable fall to its

water courses, and many sites are occupied.

Because responsible statistical data is usually

accorded unqualified credence, it is without undue hesitation that the

following bit of astonishing information, gleaned from a reliable source, is

here set down as positive proof of the excellence of Loudoun's climate:

"It (Leesburg) is located in a section the healthiest in the world, as

proven by statistics which place the death rate at 8-1/2 per 1,000, the very

lowest in the table of mortality gathered from all parts of the habitable

globe."

The climate of Loudoun, like that of most other

localities, is governed mainly by the direction of the prevailing winds, and,

to a limited extent, is influenced by the county's diversified physical

features.

Though the rainfall is abundant, amounting

annually to forty or fifty inches, ordinarily the air is dry and salubrious.

This ample precipitation is usually well distributed throughout the growing

season and is rarely insufficient or excessive. The summer rainfall comes

largely in the form of local showers, scarcely ever attended by hail. Loudoun

streams for the most part are pure and rapid, and there appears to be no local

cause to generate malaria.

In common with the rest of

Loudoun winters are not of long duration and are

seldom [26]marked by protracted severity.

Snow does not cover the ground for any considerable period and the number of

bright sunny days during these seasons is unusually large. In their extremes of

cold they are less rigorous than the average winters of sections farther north

or even of western localities of the same latitude. Consequently the growing

season here is much more extended than in either of those sections. The

prevailing winds in winter are from the north and west, and from these the

mountains afford partial protection.

The seasons are somewhat earlier even than in

the

Loudoun summers, as a rule, are long and

agreeably cool, while occasional periods of extreme heat are not more

oppressive than in many portions of the North. The mountains of Loudoun have a

delightful summer climate coupled with inspiring scenery, and are well known as

the resort of hundreds seeking rest, recreation, or the restoration of health.

This region, owing to its low humidity, has little dew at night, and

accordingly has been found especially beneficial for consumptives and those

afflicted with pulmonary diseases. The genial southwest trade winds, blowing

through the long parallel valleys, impart to them and the enclosing mountains

moisture borne from the far away

The geology of more than half the area of

Loudoun County has received thorough and intelligent treatment at the hands of

Arthur Keith in his most excellent work entitled "Geology of the

Catoctin Belt," authorized and published by the United States

Geological Survey.[5]

[5] Credit for many important

disclosures and much of the detail appearing in this department is unreservedly

accorded Mr. Keith and his assistants.[27]

Mr. Keith's analysis covered the whole of

[6] The name "Catoctin

Belt" is applied to this region because it is separated by

In this important work the Catoctin Belt is

shown to be an epitome of the leading events of geologic history in the

Appalachian region. It contains the earliest formations whose original

character can be certified; it contains almost the latest known formations; and

the record is unusually full, with the exception of the later Paleozoic rocks.

Its structures embrace nearly every known type of deformation. It furnishes

examples of every process of erosion, of topography derived from rocks of

nearly every variety of composition, and of topography derived from all types

of structure except the flat plateau type. In the recurrence of its main

geographic features from pre-Cambrian time till the present day it furnishes a

remarkable and unique example of the permanence of continental form.

With certain qualifications, a summary of the

leading events that have left their impress on the region is as follows:

1. Surface eruption of diabase.

2. Injection of granite.

3. Erosion.

4. Surface eruption of quartz-porphyry,

rhyolite, and andesite.

5. Surface eruption of diabase.

6. Erosion.

7. Submergence, deposition of Cambrian

formations; slight oscillations during their deposition; reduction of land to

baselevel.

8. Eastward tilting and deposition of

Martinsburg shale; oscillations during later Paleozoic time.

9. Uplift, post-Carboniferous deformation and

erosion.

10. Depression and

11. Uplift,

12. Depression and deposition of Potomac, Magothy,

and

13. Uplift southwestward and erosion to

baselevel.

14. Uplift, warping and degradation to Tertiary

baselevel; deposition of Pamunkey and

15. Depression and deposition of

16. Uplift and erosion to lower Tertiary

baselevel.

17. Uplift, warping and erosion to Pleistocene

baselevel; deposition of high-level

18. Uplift and erosion to lower Pleistocene

baselevel; deposition of low-level

19. Uplift and present erosion.

Along the Coastal plain reduction to baselevel

was followed by depression and deposition of Lafayette gravels; elevation

followed and erosion of minor baselevels; second depression followed and

deposition of Columbia gravels; again comes elevation and excavation of narrow

valleys; then depression and deposition of low-level Columbia; last, elevation

and channeling, which is proceeding at present. Along the Catoctin Belt

denudation to baselevel was followed by depression and deposition of gravels; elevation

followed and erosion of minor baselevels among the softer rocks; second

depression followed, with possible gravel deposits; elevation came next with

excavation of broad bottoms; last, elevation and channeling, at present in

progress.

The general structure of the Catoctin Belt is

anticlinal. On its core appear the oldest rocks; on its borders, those of

medium age; and in adjacent provinces the younger rocks. In the location of its

system of faulting, also, it faithfully follows the Appalachian law that faults

lie upon the steep side of anticlines.[29]

After the initial location of the folds along

these lines, compression and deformation continued. Yielding took place in the

different rocks according to their constitution.

Into this system of folds the drainage lines

carved their way. On the anticlines were developed the chief streams, and the

synclines were left till the last. The initial tendency to synclinal ridges was

obviated in places by the weakness of the rocks situated in the synclines, but

even then the tendency to retain elevation is apt to cause low ridges. The

drainage of the belt as a whole is anticlinal to a marked degree, for the three

main synclinal lines are lines of great elevation, and the anticlines are

invariably valleys.

In order of solubility the rocks of the Catoctin

Belt, within the limits of

1.

2.

3.

4. Granite; feldspathic.

5. Loudoun formation; feldspathic.

6. Granite and schist; feldspathic.

7. Catoctin schist; epidotic and feldspathic.

8. Weverton sandstone; siliceous.

All of these formations are in places reduced to

baselevel. The first three invariably are, unless protected by a harder rock;

the next three usually are; the Catoctin schist only in small parts of its

area; the Weverton only along a small part of

The Catoctin Belt itself may be described as a

broad area of igneous rocks bordered by two lines of Lower Cambrian sandstones

and slates. Over the surface of the igneous rocks are scattered occasional

outliers of the Lower Cambrian slate; but far the greater part of the surface

of the belt is covered by the igneous rocks. The belt as a whole may be

regarded as an anticline, the igneous rocks constituting the core, the [30]Lower Cambrian the flanks,

and the Silurian and

They are the oldest rocks in the Catoctin Belt

and occupy most of its area. They are also prominent from their unusual

character and rarity.

An important class of rocks occurring in the

Catoctin Belt is the sedimentary series. It is all included in the Cambrian

period and consists of limestone, shale, sandstone and conglomerate. The two

border zones of the Catoctin Belt, however, contain also rocks of the Silurian

and Juratrias periods. In general, the sediments are sandy and calcareous in

the Juratrias area, and sandy in the Catoctin Belt. They have been the theme of

considerable literature, owing to their great extent and prominence in the

topography.

The granite in the southern portion of the

County is very important in point of extent, almost as much so as the diabase

in the same section.

The areas of granite are, as a rule, long narrow

belts, and vary greatly in width.

The mineralogical composition of the granite is

quite constant over large areas. Six varieties can be distinguished, however,

each with a considerable areal extent. The essential constituents are quartz,

orthoclase and plagioclase, and by the addition to these of biotite, garnet,

epidote, blue quartz, and hornblende, five types are formed. All these types

are holocrystalline, and range in texture from coarse granite with augen an

inch long down to a fine epidote granite with scarcely visible crystals.

Among the various Cambrian formations of the

Catoctin Belt there are wide differences in uniformity and composition. [31]In none is it more

manifest than in the first or Loudoun formation. This was theoretically to be

expected, for first deposits upon a crystalline foundation represent great

changes and transition periods of adjustment among new currents and sources of

supply. The Loudoun formation, indeed, runs the whole gamut of sedimentary possibilities, and that within very short geographical

limits. Five miles northwest of Aldie the Loudoun formation comprises

limestone, slate, sandy slate, sandstone, and conglomerate with pebbles as

large as hickory nuts. These amount in thickness to fully 800 feet, while less

than three miles to the east the entire formation is represented by eight or

ten feet of black slate.

The name of the Loudoun formation is given on

account of the frequent occurrence of all its variations in

The Loudoun formation, of course, followed a

period of erosion of the Catoctin Belt, since it is the first subaqueous

deposit. It is especially developed with respect to thickness and coarseness to

the west of

The distribution of the coarse varieties

coincides closely with the areas of greatest thickness and also with the

synclines in which no Weverton sandstone appears. The conglomerates of the

Loudoun formation are composed of epidotic schist, andesite, quartz, granite,

epidote, and jasper pebbles embedded in a matrix of black slate and are very

limited in extent.

The formation next succeeding the Loudoun

formation is the Weverton sandstone. It is so named on account of its prominent

outcrops in

From the distribution of these various

fragments, inconspicuous as they are, considerable can be deduced in regard to

the environment of the Weverton sandstone.[33]

The submergence of the Catoctin Belt was

practically complete, because the Weverton sandstone nowhere touches the

crystalline rocks. Perhaps it were better stated that submergence was complete

in the basins in which Weverton sandstone now appears. Beyond these basins, however,

it is questionable if the submergence was complete, because in the Weverton

sandstone itself are numerous fragments which could

have been derived only from the granite masses. These fragments consist of blue

quartz, white quartz, and feldspar. The blue quartz fragments are confined

almost exclusively to the outcrops of the Weverton sandstone in the Blue Ridge

south of the

The general grouping of the Loudoun formation

into two classes of deposit (1), the fine slates associated with the Weverton

sandstone, and (2), the course sandstones occurring in deep synclines with no

Weverton, raises the question of the unity of that formation. The evidence on

this point is manifold and apparently conclusive. The general composition of

the two is the same—i. e., beds of feldspathic, siliceous material derived from

crystalline rocks. They are similarly metamorphosed in different localities.

The upper parts of the thicker series are slates identical in appearance with

the slates under the Weverton, which presumably represent the upper Loudoun.

A marked change in the thickness of the Weverton

sandstone occurs along

Aside from this marked change in thickness, none

of unusual extent appears in the Weverton sandstone over the remainder of the

Catoctin Belt. While this is partly due to lack of complete sections, yet such

as are complete show a substantial uniformity. The sections of the

An epoch of which a sedimentary record remains

in the region of the Catoctin Belt is one of submergence and deposition, the

At the

As a whole the formation is a large body of red

calcareous and argillaceous sandstone and shale. Into this, along the [35]northern portion of the Catoctin

Belt, are intercalated considerable wedges or lenses of limestone conglomerate.

At many places also gray feldspathic sandstones and basal conglomerates appear.

The limestone conglomerate is best developed

from the Potomac to Leesburg, and from that region southward rapidly diminishes

until it is barely represented at the south end of

The conglomerate is made up of pebbles of

limestone of varying sizes, reaching in some cases a foot in diameter, but, as

a rule, averaging about 2 or 3 inches. The pebbles are usually well rounded,

but sometimes show considerable angles. The pebbles of limestone range in color

from gray to blue and dark blue, and occasionally pebbles of a fine white

marble are seen; with rare exceptions also pebbles of Catoctin schist and

quartz occur. They are embedded in a red calcareous matrix, sometimes with a

slight admixture of sand. As a rule the entire mass is calcareous.

The conglomerate occurs, as has been said, in

lenses or wedges in the sandstone ranging from 1 foot to 500 feet in thickness,

or possibly even greater. They disappear through complete replacement by

sandstone at the same horizon. The wedge may thin out to a feather edge or may

be bodily replaced upon its strike by sandstone; one method is perhaps as

common as the other. The arrangement of the wedges is very instructive indeed.

The general strike of the

The result of weathering upon the conglomerate

is a very uneven and rugged series of outcrops projecting above the rolling

surface of the soil.

The ledges show little definite stratification

and very little dip. The topography of the conglomerate is inconspicuous and

consists of a slightly rolling valley without particular features. It

approaches nearer to the level of the present drainage than any other

formation, and decay by solution has gone on to a very considerable extent.

Where the draining streams have approached their baselevel, scarcely an outcrop

of conglomerate is seen. Where the areas of conglomerate lie near faster

falling streams, the irregular masses of unweathered rocks appear.

When but slightly weathered the conglomerate

forms an effective decorative stone and has been extensively used as a marble

with the name "Potomac marble," from the quarries on the Potomac east

of

The thickness of the

Description of the lithified deposits would be

far from complete without reference to the later diabase which is associated

with the

These diabases, as they will be called

generically, are usually composed of plagioclase feldspar, and diallage or

augite; additional and rarer minerals are quartz, olivine, hypersthene,

magnetite, ilmenite, and hornblende. Their structure is ophitic in the finer varieties, and to some extent in the coarser kinds as well.

They are holocrystalline in [37]form and true glassy bases are rare, rendering the term diabase

more appropriate than basalt.

There is greater variety in texture, from fine

aphanitic traps up to coarse grained dolerites with feldspars one-third of an

inch long. The coarser varieties are easily quarried and are often used for

building stone under the name of granite.

These forms are retained to the present day with

no material change except that of immediate weathering, but to alterations of

this kind they are an easy prey, and yield the most characteristic forms. The

narrow dikes produce ridges between slight valleys of sandstone or shale, the wide bodies produce broad flat hills or uplands.

The rock weathers into a fine gray and brown clay with

numerous bowlders of unaltered rock of a marked concentric shape.

While the diabase dikes are most prominent in

the

The diabase occurs only as an intrusive rock in

the vicinity of the Catoctin Belt. Of this form of occurrence, however, there

are two types, dikes and massive sheets or masses. The dikes are parallel to

the strike of the inclosing sandstone as a rule, and appear to have their

courses controlled by it on account of their small bulk. The large masses break

at random across the sandstone in the most eccentric fashion. No dislocation

can be detected in the sandstones, either in strike or dip, yet of course it must

exist by at least the thickness of the intrusive mass. That this thickness is

considerable is shown by the coarseness of the larger trap masses, which could

occur only in bodies of considerable size, and also by the width of their

outcrops in the westward dipping sandstones. The chief mass in point of size is

three miles wide. This mass fast decreases in width as it goes north, without [38]losing much of its coarseness,

and ends in Leesburg in a hooked curve. The outline of the diabase is

suggestive of the flexed trap sheets of more northern regions, but this

appearance is deceptive, since the diabase breaks directly across both red

sandstone and limestone conglomerate, which have a constant north and south

strike. An eastern branch of this mass crosses the Potomac as a small dike and

passes north into

At Leesburg the limestone conglomerate next the

diabase is indurated, its iron oxide is driven off, and the limestone partly

crystallized into marble.

The Catoctin schist is geographically the most

important of the volcanic rocks of Loudoun.

Throughout its entire area the schist is

singularly uniform in appearance, so that only two divisions can be made with

any certainty at all. These are dependent upon a secondary characteristic, viz,

the presence of epidote in large or small quantities. The epidote occurs in the

form of lenses arranged parallel to the planes of schistosity, reaching as high

as five feet in thickness and grading from that down to the size of minute

grains. Accompanying this lenticular epidote is a large development of quartz in

lenses, which, however, do not attain quite such a size as those of epidote.

Both the quartz and epidote are practically insoluble and lie scattered over

the surface in blocks of all sizes. In places they form an almost complete

carpet and protect the surface from removal. The resulting soil, where not too

heavily encumbered with the epidote blocks, is rich and well adapted to

farming, on account of the potash and calcium contained in the epidote and

feldspar.

Except along the narrow

canyons in the Tertiary baselevel the rock is rarely seen unless badly

weathered.

The light [39]bluish green color of the

fresh rock changes on exposure to a dull gray or yellow, and the massive ledges

and slabs split up into thin schistose layers. It is quite compact in appearance,

and as a rule very few macroscopic crystals can be seen in it.

A general separation can be made into an

epidotic division characterized by an abundance of macroscopic epidote and a

non-epidotic division with microscopic epidote. These divisions are accented by

the general finer texture of the epidotic schist.

The schists can be definitely called volcanic in

many cases, from macroscopic characters, such as the component minerals and

basaltic arrangement. In most cases, the services of the microscope are

necessary to determine their nature. Many varieties have lost all of their

original character in the secondary schistosity. None the less, its origin as

diabase can definitely be asserted of the whole mass. In view of the fact,

however, that most of the formation has a well defined schistosity destroying

its diabasic characters, and now is not a diabase but a

schist, it seems advisable to speak of it as a schist.

Sections of the finer

schist in polarized light show many small areas of quartz and plagioclase and

numerous crystals of epidote, magnetite, and chlorite, the whole having a

marked parallel arrangement. Only in the coarser varieties is the real

nature of the rock apparent. In these the ophitic arrangement of the coarse

feldspars is well defined, and in spite of their subsequent alteration the

fragments retain the crystal outlines and polarize together. Additional

minerals found in the coarse schists are calcite, ilmenite, skeleton oblivine,

biotite, and hematite.

The Piedmont plain, where it borders upon the

Catoctin Belt, is composed in the main of the previously described

The rocks, in a transverse line, beginning a

little to the east of Dranesville, in Fairfax County, and extending to the

Catoctin Mountain, near Leesburg, occur in the following order, viz: Red

sandstone, red shale, greenstone, trap, reddish slate, and conglomerate

limestone.

Heavy dykes of trap rock extend across the lower

end of the County, from near the mouth of

[7]

[8] Ibid.

A great class of

variations due to rock character are those of surface form. The rocks have been

exposed to the action of erosion during many epochs, and have yielded

differently according to their natures. Different stages in the process of

erosion can be distinguished and to some extent correlated with the time scale

of the rocks in other regions. One such stage is particularly manifest in the

Catoctin Belt and furnishes the datum by which to place other stages. It is

also best adapted for study, because it is connected directly with the usual

time scale by its associated deposits. This stage is the Tertiary baselevel,

and the deposit is the

The materials of the

Dynamic metamorphism has produced great

rearrangement of the minerals along the eastern side of the Catoctin Belt, [42]and results at times in

complete obliteration of the characters of the granite. The first step in the

change was the cracking of the quartz and feldspar crystals and development of

muscovite and chlorite in the cracks. This was accompanied by a growth of

muscovite and quartz in the unbroken feldspar. The aspect of the rock at this

stage is that of a gneiss with rather indefinite

banding. Further action reduced the rock to a collection of angular and rounded

fragments of granite, quartz, and feldspar in a matrix of quartz and mica, the

mica lapping around the fragments and rudely parallel to their surfaces. The

last stage was complete pulverization of the fragments and elongation into

lenses, the feldspathic material entirely recomposing into muscovite, chlorite,

and quartz, and the whole mass receiving a strong schistosity, due to the

arrangement of the mica plates parallel to the elongation. This final stage is

macroscopically nothing more than a siliceous slate or schist, and is barely

distinguishable from the end products of similar metamorphism in the more

feldspathic schists and the Loudoun sandy slates. The different steps can

readily be traced, however, both in the hand specimen and under the microscope.

The Weverton sandstone has suffered less from

metamorphism than any of the sediments. In the

Metamorphism of the Loudoun formation is quite

general. It commonly appears in the production of phyllites from the [43]argillaceous members of the

formation, but all of the fragmental varieties show some elongation and

production of secondary mica. The limestone beds are often metamorphosed to

marble, but only in the eastern belt. The recrystallization is not very

extensive, and none of the marbles are coarse grained.

The metamorphism of the igneous rocks is

regional in nature and has the same increase from west to east as the

sediments.

In the granite it consists of various stages of

change in form, attended by some chemical rearrangement. The process consisted

of progressive fracture and reduction of the crystals of quartz and feldspar,

and was facilitated by the frequent cleavage cracks of the large feldspars. It

produced effects varying from granite with a rude gneissoid appearance, through

a banded fine gneiss, into a fine quartz schist or

slate. These slaty and gneissoid planes are seen to be parallel to the

direction and attitude of the sediments, wherever they are near enough for

comparison.

Dynamic alteration of the Catoctin diabase is

pronounced and wide-spread. Macroscopically it is evident in the strong

schistosity, which is parallel to the structural planes of the sediments when

the two are in contact. In most areas this alteration is mainly chemical and

has not affected the original proportions of the rock to a marked extent. Its

prevalence is due to the unstable composition of the original minerals of the

rock, such as olivine, hypersthene, and pyroxene. Along

The average dip of the schistose planes is about

60°; from this they vary up to 90° and down to 20°. In all cases they are

closely parallel to the planes on which the sediments moved in adjustment to

folding, namely, the bedding planes. In regions where no sediments occur, the

relation of the schistose planes to the folds can not be discovered.[44]

Parallel with the micas that cause the

schistosity, the growth of the quartz and epidote lenses took place. These,

too, have been deformed by crushing and stretching along

The ratios of schistose deformation in the

igneous rocks are as follows: diabase, with unstable mineral composition and

small mechanical strength, has yielded to an extreme degree; granite, with

stable composition and moderate mechanical strength, has yielded to the more

pronounced compression.

In point of mineral wealth Loudoun ranks with

the foremost counties of the State. Iron, copper, silver, soapstone, asbestos,

hydraulic limestone, barytes, and marble are some of the deposits that have

been developed and worked with a greater or lesser degree of success.

A large bed of compact red oxide of iron lies at

the eastern base of the

Magnetic iron ore has been found in certain

places, and this or a similar substance has a disturbing effect upon the [45]needle of the surveyor's

compass, rendering surveying extremely difficult where great accuracy is

required. In some instances the needle has been drawn as much as seven degrees

from its true course. This effect is more or less observable nearly throughout

the

Chromate of iron was long ago discovered along

Broad Run, and, about the same time, a bed of micaceous iron ore on

In 1860, the output of pig iron in Loudoun was

2,250 tons, and its value $58,000. Rockbridge was the only

In several localities small angular lumps of a

yellowish substance, supposed to contain sulphur, have been found, embedded in

rocks. When subjected to an intense heat, it gives forth a pungent sulphurous

odor.

Small quantities of silver ore are discovered

from time to time; but the leads have never been extensively worked and many of

the richest veins are still untouched.

Deposits of copper in the schists have long

excited interest and led to mining operations. The amount of ore, however,

appears not to have justified any considerable work.

Near the base of the

In the vicinity of Leesburg and north of that

town, and between the

The exhibition at the World's Fair, at

1. Specular Iron Ore, from near Leesburg,

said to be in quantity. From Professor Fontaine.

2. Chalcopyrite, from near Leesburg, said

to be a promising vein. From Professor Fontaine.

The following were contributed by the

"Eagle Mining Company," of Leesburg; F. A. Wise, general manager:

1. Carbonate of Copper, from vein 3'

wide, developed to 25' deep. Assays by Oxford Copper Company of

2. Sulphuret of Copper, from vein

10" wide, developed to 50' deep. Assays by Oxford Copper Company of

3. Iron

4. Sulphuret of Copper, from vein

developed 50'. Yields 11 per cent of copper and 1 ounce of

silver per ton by assay of W. P. Lawver, U. S. Mint.

5. Carbonate of Copper, red oxide and

glance, from vein 3' wide, developed to 25' deep. Yields 50 per cent metallic

copper and 27 ounces silver per ton by assays.[47]

6. Iron

7. Oxide of Copper, from Carbonate vein,

developed 60' on 4' wide vein; 25' deep.

8. Sulphuret of Copper, from vein 8"

to 15" wide, developed 50'.

9. Iron

10. Barytes, heavy spar, vein

undeveloped.

11. Iron

12. Marble, from quarry of "Virginia

Marble Company," three miles east from Middleburg. The deposit has been

demonstrated to be of great extent; the marble has been pronounced of a very

superior quality. Contributed by Major B. P. Noland.

13. Marble, from same as above.

14. Marble, from same as above.

17. Copper

In the "Handbook on the Minerals and

Mineral Resources of Virginia" prepared by the Virginia Commission to

the St. Louis Exposition, Loudoun is credited with the three comparatively rare

minerals given below. The two first-named occur nowhere else in the State.

"Actinqlite:

Calcium-magnesium-iron, Amphibole,

Ca (Mg Fe)3(Si

O4)3.

Specific Gravity, 3-3.2. Hardness, 5-6. Streak,

uncolored.... Fine radiated olive-green crystals are found ... at

Taylorstown...."

"Tremolite: A variety of

Amphibole. Calcium.

Magnesium Amphibole. Ca Mg2(Si

O4)3.

Specific Gravity, 2.9-3.1. Hardness,

5.6. Long bladed crystals; also columnar and fibrous.

Color, white and grayish. [48]Sometimes nearly transparent. Found in the greenish

talcose rocks at Taylorstown."

Chromite, of which no occurrence

of economic importance has yet been discovered in the County or elsewhere in

"[9]On the eastern

flank of the Catoctin rests a thin belt of mica slate. This rock is composed of

quartz and mica in varying proportions, and this belt, on reaching the Bull Run

Mountain, there expands itself, and forms the whole base of that mountain, and

where the mica predominates, as it does there, it sometimes forms excellent

flagging stones."

[9]

"Immediately at the western base of the

"Along the eastern side of the valley (Loudoun)

gneiss is frequently met with on the surface, and where the larger streams have

worn deep valleys, it is sometimes exposed in high and precipitous cliffs. This

is more particularly the case along

"Another rock that is a valuable

acquisition is hornblende. This kind when first taken from the ground, is always covered as with a coat of rust. This is

doubtless the fact, for the oxydasion of the iron it contains gives it that appearance,

and colors the soil a reddish hue in its immediate vicinity. Wherever this rock

abounds, the soil is durable and the crops are usually heavy. It is sometimes

met with having a fine grain, and so very hard as to be almost brittle, though

generally very difficult to break, and when broken strongly resembling cast-iron, and will sometimes ring, on being struck, almost

as clearly. It was used very much formerly for making journals to run

mill-gudgeons upon. When found on the surface, it is usually of a rounded

form...."

However, much of the rock of the valley partakes

of the nature of both hornblend and gneiss, and has been aptly termed a

"hornblend gneiss rock."

Beds of magnesian or talcose slate, sometimes

containing crystals of sulphuret of iron, are frequently met with in this

section, and at the base of Black Oak Ridge, which is composed chiefly of

chlorite slate and epidote, another bed of magnesian limestone is found.

Containing about 40 per cent of magnesia, it makes an

excellent cement for walls, but is of little or no value as a

fertilizer.

SOILS.[10]

The soils of Loudoun vary greatly in both

geological character and productiveness, every variety from a rich alluvial to an unproductive clay occurring within her boundaries. In

general the soils are deep and rich and profitably cultivated.

The heavy clay soils of Loudoun are recognized

as being the strongest wheat and grass soils. The more loamy soils are better

for corn on account of the possibility of more thorough cultivation. However,

the lands all have to be fertilized or limed to obtain the best results, and

with this added [50]expense the profit in wheat growing is extremely uncertain

on any but the clay soils. The loamy soils are especially adapted to corn,

stock raising, and dairying, and they are largely used

for these purposes. The mountain sandstone soils, which are rough and stony,

are not adapted to any form of agriculture; but for some lines of

horticulture—as, for instance, the production of grapes, peaches, apples and

chestnuts—or forestry they seem to offer excellent opportunities. The schist

soil of the mountains, although rough and stony, is productive, easily worked,

and especially adapted to apples, peaches, and potatoes. The shale and mica

soils, although thin and leachy, are especially adapted to grapes, vegetables,

and berries, and other small fruits. These soils should be managed very

carefully to obtain the best results. They are easily worked and very quickly

respond to fertilization and thorough cultivation. It is very probable that

market gardening and fruit raising on these types

would prove profitable. It seems, however, that peach trees are short lived on

these soils. The meadow lands are low and subject to overflow, although

otherwise well drained. They are best adapted to the production of corn, grass,

and vegetables.

[10] For the bulk of the

information appearing under this caption the author is indebted to Carter's and

Lyman's Soil Survey of the Leesburg Area, published in 1904 by the

United States Department of Agriculture.

That part of the County lying east of a line

drawn from the Potomac River near Leesburg, by Aldie to the Fauquier line, is

much more unproductive than the western portion, partly on account of an

inferior soil, and partly in consequence of an exhausting system of cultivation,

once so common in eastern Virginia, i. e., cropping with corn and tobacco

without attempting to improve the quality of the soil. When impoverished, the

lands were thrown out to the commons.

Large tracts that formerly produced from thirty

to forty bushels of corn to the acre, still remain out

of cultivation, though many of the present proprietors are turning their

attention to the improvement of these soils and are being richly rewarded.

In this section, particularly along

Near the

[11]

[12] Ibid.

There is a huge belt of red land, known as

"the red sandstone formation," extending from the Potomac through a

part of each of the counties of Loudoun, Fairfax, Prince William,

Fauquier, Culpeper, and

Bottom lands of inexhaustible fertility and rich

upland loams are commonly met with north and south of Leesburg for a

considerable distance on either side of the turnpike leading from

Limestone occurs in vast quantities throughout

this zone, and there are present all the propitious elements that will be

enumerated in the treatment of the soils of other areas.

The land here is in a high state of cultivation

and, according to its peculiarly varying and unalterable adaptability, produces

enormous crops of all the staple grains of the County.

The soil in the vicinity of Oatlands, included

in this zone, is stiff and stony, except such as is adjacent to water courses,

or the base of hills, where it is enriched by liberal supplies of decayed

matter, which render it loamy and inexhaustible. In the main, it is of a

generous quality, so pertinaciously retaining fertilizers as to withstand the

washing of the heaviest rains. Still it is an anomaly that some of the richest areas

in this region will not produce wheat; while, in the cultivation of rye, oats,

and corn, satisfactory results are almost invariably obtained. Likewise there

are but a few parcels whereon white clover does not grow spontaneously and in

the greatest abundance. Than these, better pasture lands are found nowhere east

of the

In the

The Loudoun sandy loam consists of from 8 to 12

inches of a heavy brown or gray sandy loam, underlain by a heavy yellow or red

loam or clay loam. Often the subsoil contains a considerable quantity of coarse

sand, making the texture much the same as that of the soil. The sand of the

soil and subsoil is composed of very coarse rounded and subangular quartz

particles. The surface material is not a light sandy loam, but is more like a

loam containing considerable quantities of very coarse quartz fragments. It is

generally quite free from stones, but small areas are occasionally covered with

from 5 to 20 per cent of angular quartz fragments several inches in diameter.

The Loudoun sandy loam occurs in irregular areas

of considerable size in the intermediate valley between the Blue Ridge, Short

Hill, and

The topography of this soil in the valley varies

from gently rolling to hilly, the slopes being long and gently undulating,

while along the valley walls and in the uplands it is ridgy. Owing to the

position which this type occupies, surface drainage is good. The light texture

of the soil admits of the easy percolation of water through it, and, except

where the subsoil contains considerable sand, the soil moisture is well

retained. In dry weather, if the ground is cultivated, a mulch is formed, which

prevents the evaporation of the soil moisture and greatly assists the crops to

withstand drought.

Nearly the whole of this type is in cultivation.

Where the forest still stands the growth consists chiefly of oak. The soil is

easy to handle, and can be worked without regard to moisture content. It is

considered a good corn land, but is too light-textured for wheat, although a

considerable acreage is devoted to this crop. Corn yields at the rate of 40 or

50 bushels per acre, wheat from 12 to 15 bushels and occasionally more, and

grass and clover at the rate of 1 or 2 tons per acre. The productiveness of the

soil depends greatly on the sand content of the subsoil. If the quantity be

large, the soil is [54]porous and requires considerable rain to produce good

yields. If the clay content predominates, a moderate amount of rain suffices

and good yields are obtained. Apples, pears, and small fruits do well on this

soil.

The Penn clay consists of from 6 to 12 inches of

a red or reddish-brown loam, resting upon a subsoil of heavy red clay. The soil

and subsoil generally have the Indian-red color characteristic of the Triassic

red sandstone from which the soil is in part derived. From 1 to 10 per cent of

the soil mass is usually made up of small sandstone fragments, while throughout

the greater part of the type numerous limestone conglomerate ledges,

interbedded with Triassic red sandstone, come to the surface. In other areas of

the type numerous limestone conglomerate bowlders, often of great size, cover

from 10 to 25 per cent of the surface.

This latter phase occurs in the vicinity of the

Potomac River near Point of Rocks,

In a great many places along the base of the

mountain the formation of this type is somewhat complicated by the wash from

the mountain, which consists principally of subangular quartz fragments, from 1

to 4 inches in diameter. This rock sometimes forms as much as 30 or 40 per cent

of the soil mass. This phase is called "gravelly land," and is hard

to cultivate on account of its heavy texture and stony condition, although it

is inherently productive.[55]

This type occurs in one irregular-shaped area,

about 15 miles long, varying from less than 1 mile to 3 or 4 miles in width,

being cut by the Potomac River just east of

The general surface drainage is good, there

being many small streams flowing through the type and emptying into the

Corn, wheat, clover, and grass are the crops

grown, of which the yields are as follows: Corn, from 40 to 60 bushels per

acre; wheat, from 15 to 25 bushels per acre, and clover and grass, from 1-1/2

to 2-1/2 tons of hay per acre.

The Penn clay is the most highly prized soil of

the Piedmont region of Loudoun and brings the highest prices.

The Penn stony loam consists of from 8 to 12

inches of a red or grayish heavy loam, somewhat silty, underlain by a heavier

red loam. From 10 to 60 per cent of gray and brown fragments of Triassic

sandstone, ranging from 1 to 6 inches in thickness, cover the surface of the

soil. The color is in general the dark Indian-red of the other soils derived

from Triassic sandstone, being particularly marked in the subsoil.

This type occurs in the southeastern part of Loudoun,

on the Piedmont Plateau. It occupies three small areas whose [56]total extent probably does

not exceed two and one-half square miles. It is closely associated with the

Penn loam and grades gradually into that type. The only great difference

between the two is the presence of sandstone fragments in the Penn stony loam.

The topography varies from gently rolling to

hilly and ridgy, with slopes that are sometimes rather steep. However, the

surface is not so broken as to interfere with cultivation, and the slopes are

usually gentle.

The type is well drained, the slopes allowing a

rapid flow of water from the surface, while the soil water passes readily

through the soil and subsoil. On the other hand, the texture is sufficiently

heavy to prevent undue leaching and drought.

Little of the land is in cultivation, on account

of its stony character, which makes cultivation difficult. Where unimproved it

is covered with a heavy growth of chestnut, oak, and pine. The land is locally

called "chestnut land." In a few small areas the larger stones have

been removed and the land is cultivated, corn and wheat being the principal

crops. The yield of corn ranges from 20 to 35 bushels and of wheat from 8 to 15

bushels per acre. Apples and small fruits and vegetables do well.

The soil of the Iredell clay loam consists of

from 6 to 18 inches of light loam, usually brown or gray, although sometimes of

a yellowish color, with an average depth of about twelve inches. The subsoil

consists of a heavy yellow to yellowish-brown waxy clay. This clay is cold and

sour, almost impervious to moisture and air, and protects the underlying rock

from decay to a great extent. Often the clay grades into the rotten rock at

from 24 to 36 inches. In the poorly drained areas a few iron concretions occur

on the surface. Numerous rounded diabase bowlders, varying in size from a few

inches to several feet in diameter, are also scattered over the surface of the

soil. Occasional slopes of the type have had the soil covering entirely removed

[57]by erosion, and here,

where the clay appears on the surface, the soil is very poor. In other places,

where the soil covering is quite deep, as from 12 to 18 inches, the type is

fairly productive, and its productiveness is generally proportional to the

depth of the soil.

The local name for the Iredell clay loam is

"wax land," from the waxy nature of the subsoil, or "black-oak

land," from the timber growth. A few small, isolated areas of this soil

occur in the intermediate valley of the Catoctin Belt, and here the texture is

much the same as that described above; but the soil usually consists of from 6

to 10 inches of a drab or brown loam, underlain by a heavy

mottled yellow and drab silty clay. This phase has few stones on the surface or

in the soil. The local names for this phase are "cold, sour land" and

"white clay."

The greater part of the Iredell clay loam occurs

in the southern or southeastern corner of the County and occupies one large,

irregular-shaped but generally connected area, extending from Leesburg, in a

southeasterly and southerly direction along Goose Creek to the southern

boundary of the County, the most typical development of the soil being at

Waxpool. The phase already described occurs in small, disconnected areas,

usually quite far apart, the general relative direction of these areas being

northeast and southwest. They all lie in the intermediate valley of the

Catoctin Belt, and are usually near the foot of the

Where rolling and sloping the surface drainage

is good, the water passing rapidly from the surface into the numerous small

streams flowing into

Corn, wheat, and grass are the principal crops

grown on [58]this soil type, the average

yields per acre being as follows: Corn, from 20 to 40 bushels; wheat, from 8 to

15 bushels; and grass, from 1-1/2 to 2-1/2 tons. Apples do fairly well.

The greater part of the type is tilled, while

the uncultivated areas are used for pasturage and wood lots, the forest growth

being black oak. In dry seasons, where the soil covering is not deep, the land

bakes and cracks, and in this condition it can not be cultivated. In wet seasons

the soil becomes too wet and sticky to work.

The Penn loam consists of from 8 to 12 inches of

a dark, Indian-red loam, underlain by a heavier loam of the same color. This

peculiar red color is distinctive of the formation wherever found, and,

consequently, the type is one easily recognized. The texture of the type is

very uniform, with the exception of a few small areas where the subsoil is a

clay loam. The soil is locally termed "red-rock land," on account of

the numerous small red sandstone fragments which occur in the soil and subsoil

in quantities varying from 5 to 20 per cent of the soil mass. The soil is free

from large stones or other obstructions to cultivation.

This type occurs in several large, irregular

areas on the

The topography consists of a gently rolling to

nearly level plain, and there are no steep slopes or

rough areas. Drainage in this type is excellent, the easy slopes allowing a

gradual flow of water from the surface without undue erosion, except with very

heavy rains on the steeper slopes. The loamy subsoil allows a ready but not too

rapid percolation of surplus soil moisture, and never gets soggy or in a cold, sour condition. Numerous small streams extend throughout the

area of this type, allowing a rapid removal of all surplus water into the

The original growth on the Penn loam was a

forest of oak, hickory, and walnut, but at the present time nearly all of the

type is cleared and farmed. The soil is not naturally very productive, but is

prized on account of its great susceptibility to improvement, its quick

responsiveness to fertilization, and its easy cultivation and management. The

surface is smooth and regular, and the absence of stones, together with the

loamy texture of the soil, makes it easy to maintain good tilth. Any addition

of fertilizers or lime is immediately effective, and by judicious management

the type may be kept in a high state of productiveness. Many fine farms with

good buildings are to be seen on this type. The crops grown are corn, wheat,

grass, clover, apples, and small fruits. Grazing, stock raising,

and dairying are practiced to some extent. The land yields from 40 to 60

bushels of corn, from 10 to 15 or more bushels of wheat, and from 1 to 2 tons

of hay per acre.

The soil of the Cecil loam consists of from 8 to

12 inches of a brown or yellow loam. The subsoil consists of a heavy yellow or